In general, having a beneficiary determines who’ll receive your assets after you’re gone and ensures your financial intentions or wishes are honored. When setting up a life insurance policy, retirement account, or living trust, you should name a primary beneficiary, or the first person or entity in line to receive those assets upon your death. In case that individual dies before you or cannot be located to receive the assets, you should also name a contingent beneficiary, or the next person or entity in line. By doing so, you can avoid potential disputes and make your intentions clear.

We’ll break down the concept of various types of beneficiaries, what they mean, their roles, implications, and more. Understanding more about beneficiaries not only streamlines asset distribution but also helps prevent legal complications and family disputes. Whether you’re setting up a life insurance policy or drafting a will, clarity in beneficiary designations is essential.

What is a beneficiary?

A beneficiary, in both legal and financial contexts, is any person, entity, or organization you designate to receive benefits, rights, or assets from legal arrangements such as wills, trusts, life insurance policies, or financial accounts after your death. These designations are not just a formality; they are binding instructions that direct the transfer of your assets upon your death, often bypassing lengthy probate proceedings (except in the case of wills, since they need to be probated) and ensuring a smoother transition for your heirs.

Beneficiaries are commonly named in:

- Life insurance policies. The person who receives the insurance payout if you pass away.

- Wills and Trusts. Individuals who inherit property, money, or possessions as instructed in your wills and trust documents.

- Retirement accounts. The nominee named in your pension account, 401(k), and IRA will receive the remaining account balance.

- Bank and brokerage account. Individuals named to receive funds in a checking or savings account. These are often passed on through payable on death (POD) or transfer on death (TOD) designations.

For example, if you name your spouse as the beneficiary of your life insurance policy, the proceeds will go directly to your spouse, bypassing the probate process and any conflicting instructions in your will.

Who can be a beneficiary?

There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to choosing a beneficiary. You can choose just about anyone to inherit your assets in a living trust, will, life insurance policy, or retirement account as either a primary or contingent beneficiary—but there are some exceptions. If the designated beneficiary is under the age of majority, depending on your state, the assets would first go to a legal guardian. Naming a minor as a beneficiary could send the issue to probate court—a situation that life insurance policies and retirement accounts are designed to avoid.

Naming beneficiaries largely depends on who you want to be named as the beneficiary for your financial and other assets. The flexibility in choosing a beneficiary allows you to align your estate planning with your personal, financial, and philanthropic goals. However, your choices may be subject to specific legal or policy restrictions depending on your location and the type of account or policy involved.

You can have the following people and entities as your beneficiaries.

1. Can individuals be beneficiaries?

Most commonly, beneficiaries are individuals. These can include:

- Spouses and domestic partners. In many estate plans and insurance policies, spouses and domestic partners are the main or primary beneficiaries.

- Children and descendants. Children, who can be biological, adopted, or stepchildren, are frequently named as primary and secondary beneficiaries. When there is no spouse or partner, the decedent often names their children as their primary beneficiaries.

- Other family members. Siblings, parents, grandchildren, and extended relatives can be designated.

- Other friends and people. There is no legal requirement that a beneficiary be a family member. Close friends]or longtime companions can be named.

2. Can entities be beneficiaries?

Your beneficiary does not need to be a person. You could also name your favorite charity or nonprofit organization as a primary or contingent beneficiary, though there are additional tax implications you should consider with this option. Some of the organizations and legal entities that may qualify as entities include, but are not limited to:

- Charitable organizations. You can designate a charity, religious institution, or nonprofit as a beneficiary to support causes you care about after your death.

- Trusts. Naming a trust as a beneficiary allows you to set specific terms for how and when assets are distributed, which can be useful for minors, individuals with special needs, or complex family situations.

- Business entities. In some cases, especially in business succession planning, a corporation, LLC, or partnership might be designated as the beneficiary. You can name entities as beneficiaries in your individual retirement account (IRA) and retirement plans. Though this is less common and may have tax or legal implications, it is always good to check with a legal or tax expert while making this decision.

3. Can minor children be beneficiaries?

While minor children can be named as beneficiaries, there are legal limitations on minors receiving assets directly. In such cases, you can consider the following options:

- Holding the child’s share in trust. Assets of minor children can be held in a trust, and a trustee can be appointed to manage that trust until they reach a specified age (such as 25).

- Setting up custodial accounts. Custodial accounts are financial accounts established for minors that allow adults to transfer assets to children while maintaining control over those assets until the child reaches the age of majority. These accounts are governed by specific state laws known as the Uniform Gifts to Minors Act (UGMA) and the Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA). These accounts are managed by an adult (called the “custodian”) for the benefit of a minor (the “beneficiary”), who is typically under the age of 18 or 21, depending on state law. These accounts are commonly used by parents, grandparents, or guardians to save or invest money for a child’s future, such as for education, a first car, or other significant expenses. The UGMA and UTMA allow adults to transfer assets to minors without the need to set up a formal trust.

4. Can pets be beneficiaries?

Note that no matter how much you adore your pet, it cannot be named a beneficiary. If you’re concerned about the welfare of your pet once you’re gone, you can take care of them under your last will or living trust by leaving a specific sum of money to a pet trust that will be created for your pet after you die. In your last will or trust, you can name someone to act as the trustee of the “pet trust,” and that person will be in charge of using the funds for your pet’s benefit for the pet's lifetime.

5. Can you be your own beneficiary?

No, you cannot be your own beneficiary for life insurance, estate plans, or other financial accounts. The main purpose of having or choosing a beneficiary for your assets is to provide financial support to others if you die.

Why is naming beneficiaries important?

When planning your finances, creating a will, or setting up insurance or retirement accounts, naming beneficiaries is one of the crucial decisions. It carries significant legal and financial weight and can determine how your assets are distributed when you’re gone.

1. Ensures your wishes are honored

Naming a beneficiary gives you direct control over who receives your assets, whether it’s money from a life insurance policy, funds in a retirement account, or proceeds from an investment portfolio. Without a named beneficiary, these assets may go to unintended recipients.

2. Avoids delays

When beneficiaries aren't named for your assets, or if you haven't created a will (died intestate), your assets go through probate and are divided according to the intestacy succession laws specific to each state. On the other hand, if you have created your will or properly designated beneficiaries in your financial and retirement accounts, then your assets will pass to your intended loved ones.

Additionally, naming beneficiaries on specific accounts (or using a Trust) allows certain assets to bypass the probate process entirely. Accounts with designated beneficiaries, such as 401(k)s, IRAs, and life insurance policies, are paid directly to the named individuals, facilitating a smoother and faster transfer of assets.

3. Prevents family disputes

Clear beneficiary designations reduce the chance of confusion, conflict, or legal battles among surviving family members. Without a designated beneficiary, relatives may disagree over who is entitled to what, leading to strained relationships or costly legal challenges.

4. Minimizes legal complications

When no beneficiary is named or the named beneficiary has died, the distribution of your assets can become complicated. In such cases, the funds may need to go through probate court and then be distributed according to state law. The assets may also be subject to claims from creditors or disputes among potential heirs. Hence, naming a beneficiary helps protect assets from certain legal claims, as the transfer is direct and not part of the probate process.

5. Provides a simple and cost-effective process

Naming beneficiaries is a straightforward, cost-effective process that can be done when buying life insurance, opening bank accounts, IRAs, or at any time thereafter. It requires basic information about the chosen individuals or entities and can often be completed online. Many U.S. federal agencies now provide secure online portals for managing beneficiary designations for retirement accounts, life insurance, and other federal benefits. For example, the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) and Federal Employees' Group Life Insurance (FEGLI) programs allow federal employees to review and update their beneficiary information online. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) explicitly states that the fastest and easiest way to update your insurance beneficiary is through their Online Policy Access website. Veterans and service members with VA life insurance can log in and immediately update their beneficiary information online, ensuring their records are current and the process is streamlined. Additionally, members of the armed forces with Servicemembers’ Group Life Insurance (SGLI) coverage can manage their beneficiary designations online through the SGLI Online Enrollment System (SOES) by signing into the official milConnect portal.

However, certain complex beneficiary arrangements or agencies that have not fully transitioned to digital systems may still require paper forms or additional documentation for some changes. Always consult the official agency website to confirm the process for your specific benefit.

6. Supports estate planning goals

Beneficiary designations are a critical part of a broader estate planning strategy. They allow you to:

- Control how wealth is passed on

- Allocate specific assets to individuals or charities

- Coordinate with wills, trusts, and tax planning for optimal outcomes

- By keeping beneficiary forms updated, your estate plan stays aligned with your current wishes, life changes, and legal requirements.

7. Allows for contingency planning

Instead of naming one main beneficiary, you can also name other subsidiary beneficiaries, ensuring there’s a backup in case your primary beneficiary is unable to receive the asset. This added layer of protection helps maintain your plan’s integrity no matter what happens.

Understanding types of beneficiaries

Understanding the general types of beneficiaries helps ensure your assets are passed on efficiently, according to your wishes, and with minimal legal complications. Below is a comprehensive breakdown of the main categories of beneficiaries and how they function.

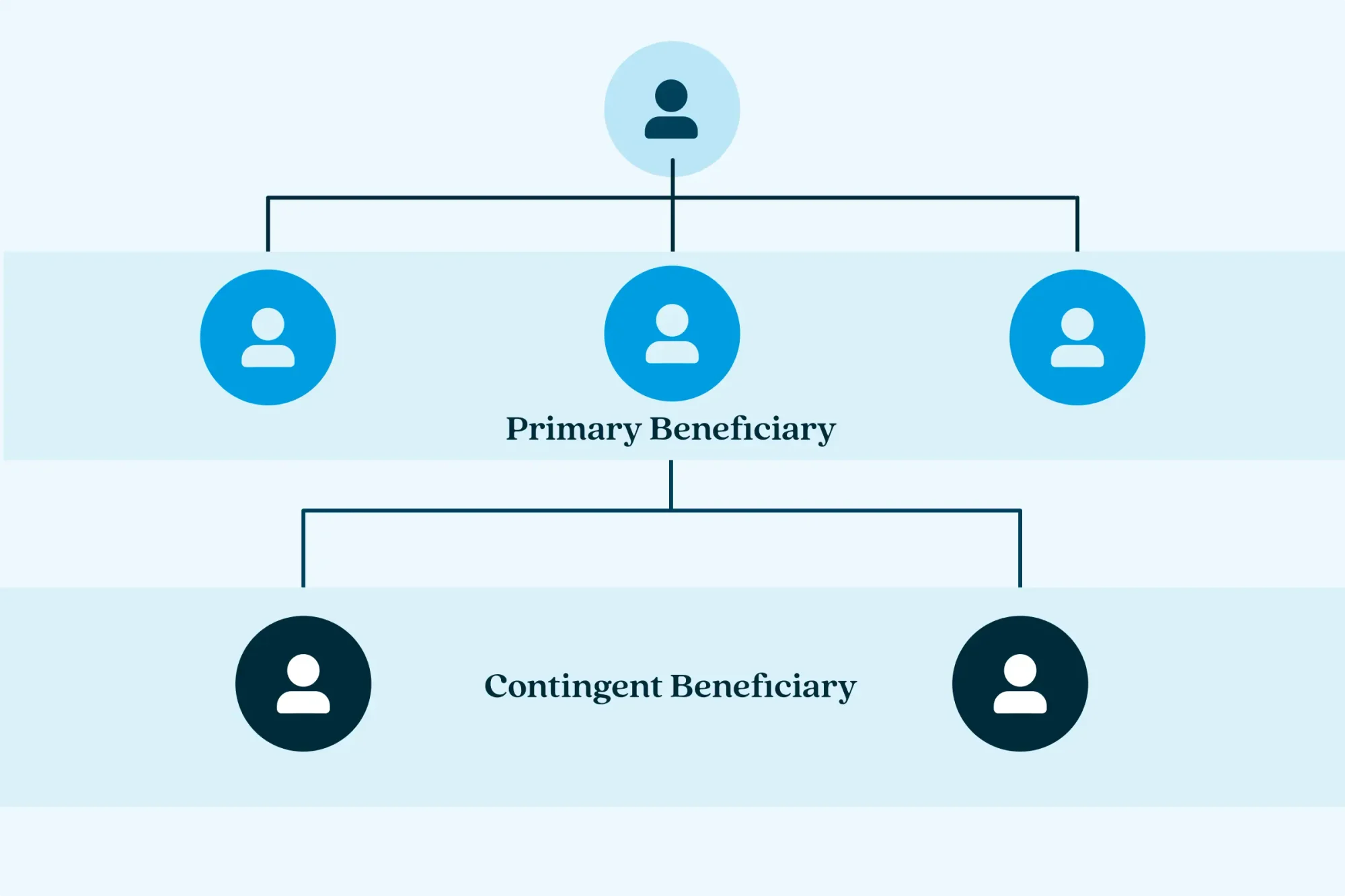

1. Primary beneficiary (principal beneficiary)

The primary beneficiary is the person or entity who has the first claim to inherit the asset after your death. Despite the term “primary,” you may name more than one such beneficiary and designate how the assets will be divided among them. Primary beneficiaries are also called principal beneficiaries interchangeably in various scenarios, but irrespective of how they’re called, the function of the primary beneficiary remains the same.

2. Contingent beneficiary (secondary beneficiary)

A contingent beneficiary, on the other hand, is the second in line to inherit the asset. The only way a contingent beneficiary inherits anything from the account or policy is if the primary beneficiary or beneficiaries have predeceased you or otherwise can’t be found.

A contingent beneficiary, also known as a secondary beneficiary, is like a backup beneficiary.

To understand better, here’s an example to explain primary beneficiary and contingent beneficiary in simpler terms.

Imagine if you have one child and one niece, and name your son as the primary beneficiary and your niece as the contingent beneficiary. Only your son would inherit the assets upon your death unless he predeceases you or can’t be found, in which case your niece would inherit the full sum. If you name them both as primary beneficiaries, they would split the assets according to the percentages you have decided on.

Alternatively, if you have a spouse, you may choose to name your spouse as the primary beneficiary and your child as the contingent beneficiary, in which case your son would inherit only if your spouse predeceases you.

3. Tertiary beneficiary

A tertiary beneficiary is the third designated recipient (person or entity), who comes after primary and contingent beneficiaries. If both primary and contingent beneficiaries cannot or are unavailable to accept the benefit, the tertiary beneficiary receives it. This designation is a further backup to ensure assets are distributed according to your wishes.

4. Specific gift beneficiary

Specific gift beneficiaries are beneficiaries who receive designated items and amounts that are specified clearly in a will or trust. You can name your primary, and contingent beneficiaries to receive specific gifts from your assets.

5. Residuary beneficiary

Residuary beneficiary is the individual or entity designated to receive the remainder (residue) of an estate in a will or a trust after all specific gifts, debts, and expenses have been distributed or paid. Naming a residuary beneficiary ensures that nothing is left unaccounted for, so any assets that are not specifically gifted are distributed according to your wishes rather than by state law.

For example, suppose your will states:

- “I leave $25,000 to each of my grandchildren.”

- “I leave my jewelry collection to my sister Susan.”

- “The rest, residue, and remainder of my estate I leave to my surviving children in equal shares.”

In this case:

- Grandchildren are specific beneficiaries (cash gifts)

- Sister Susan is also the specific beneficiary (jewelry)

- Surviving children are residuary beneficiaries

6. Co-beneficiary

A co-beneficiary refers to two or more individuals or entities who are named to receive assets from an account, policy, or estate at the same time and share in those assets according to the allocation you specify. This arrangement can apply to primary beneficiaries, contingent beneficiaries, or tertiary beneficiaries levels.

To elaborate on this, see the two scenarios below of how co-beneficiaries function.

Co-beneficiaries as primary beneficiaries

If you name more than one person as a primary beneficiary, they’re considered co-primary beneficiaries. For example, if a widower names both his adult children as primary beneficiaries of his pension account and specifies that each should receive 50%, both children are co-primary beneficiaries and each will receive half of the account upon his passing.

Co-beneficiaries as contingent beneficiaries

You can also name multiple contingent beneficiaries, making them co-contingent beneficiaries. These individuals or entities will inherit the assets only if all primary beneficiaries are unable to do so (for example, if they predecease the account owner or cannot be located).

Example: Jane names her spouse as the sole primary beneficiary of her retirement account, and her two children as co-contingent beneficiaries, each to receive 50%. If Jane’s spouse passes away before her, both children would inherit the amount equally as co-contingent beneficiaries.

7. Entity beneficiary

An entity beneficiary is a non-individual beneficiary, such as a trust, charity, or business. Entity beneficiaries can be designated at any level of the beneficiary hierarchy, just like individual beneficiaries: primary, secondary, tertiary, or any other level. The distinction between “entity” and “individual” refers to the type of beneficiary, not their position in the succession order. For example, David Chen named multiple primary beneficiaries for his retirement account. According to his allocation, he designated 50% of the amount to his daughter Jennifer Chen, 30% to the Chen Family Trust, and the remaining 20% to a local food bank (actual names of organizations and charities should be specified in your will). After he dies, the retirement amount will be divided according to the percentage shares he mentioned in his will for these three.

8. Remote beneficiary

This term is sometimes used informally to describe a beneficiary who is unlikely to receive assets, often because they are far down the line of succession, such as after primary, contingent, and tertiary beneficiaries. For example, imagine a family discussion happening between Mary and her husband about appointing beneficiaries in their will. Mary says to her husband, “I’m thinking of naming my cousin Jake as a beneficiary, but he’s really just a remote beneficiary since he’ll come after you, my kids, grandkids, parents, and my brother in line.” Remote beneficiaries can be named in most wills and trusts as a failsafe.

9. Revocable beneficiary

A revocable beneficiary is someone whose beneficiary status can be changed or revoked by the account or policy owner at any time, without the beneficiary’s consent, as long as the owner is alive. Most beneficiary designations are revocable by default.

10. Irrevocable beneficiary

An irrevocable beneficiary cannot be changed or removed without the beneficiary’s written consent. This type of designation is less common and is sometimes used in legal agreements, such as divorce settlements or certain trust arrangements.

Irrevocable beneficiary in divorce settlements

In the context of divorce, a court may require one spouse to name the other as an irrevocable beneficiary on a life insurance policy. This is often done to secure ongoing financial obligations such as child support or alimony. By making the beneficiary designation irrevocable, the policyholder cannot change or remove the ex-spouse as beneficiary without their explicit consent, providing assurance that the intended financial protection will remain in place for as long as required by the divorce agreement.

For example, if a divorce settlement stipulates that an ex-spouse must be the beneficiary of a life insurance policy to guarantee support for children, designating the ex-spouse as an irrevocable beneficiary ensures that the policyholder cannot later alter the beneficiary without the ex-spouse’s agreement. This legal safeguard helps prevent disputes and ensures compliance with the court-ordered support obligations. State law ultimately governs the rights and requirements for irrevocable beneficiaries, and courts may adjust the arrangement if circumstances change, such as when children reach adulthood or support obligations end.

It is important to consult legal and financial professionals when setting up or modifying such arrangements to ensure they are properly documented and enforceable.

Several official state statutes and courts explicitly detail the use of irrevocable beneficiaries in divorce settlements.

For instance, in Florida, Section 732.507(2) of the state statutes automatically voids a beneficiary designation for a former spouse upon divorce, unless the divorce decree or settlement specifically requires the ex-spouse to remain as an irrevocable beneficiary. This means a court can order, or parties can agree, that an ex-spouse stays as an irrevocable beneficiary to secure obligations like alimony or child support.

What is beneficiary allocation?

When you name beneficiaries on your financial accounts, life insurance policies, or estate documents, you’re not just deciding who gets what; you’re also deciding how much each person or entity should receive. That distribution is called beneficiary allocation. Proper allocation ensures your wishes are carried out, helps prevent disputes, and can have significant legal and financial consequences.

In simple terms, allocation for a beneficiary refers to the specific percentage or portion of an asset that each named beneficiary is entitled to when the account holder or policyholder passes away. For example, you might specify that 60% of your life insurance account goes to your spouse and 40% to your child.

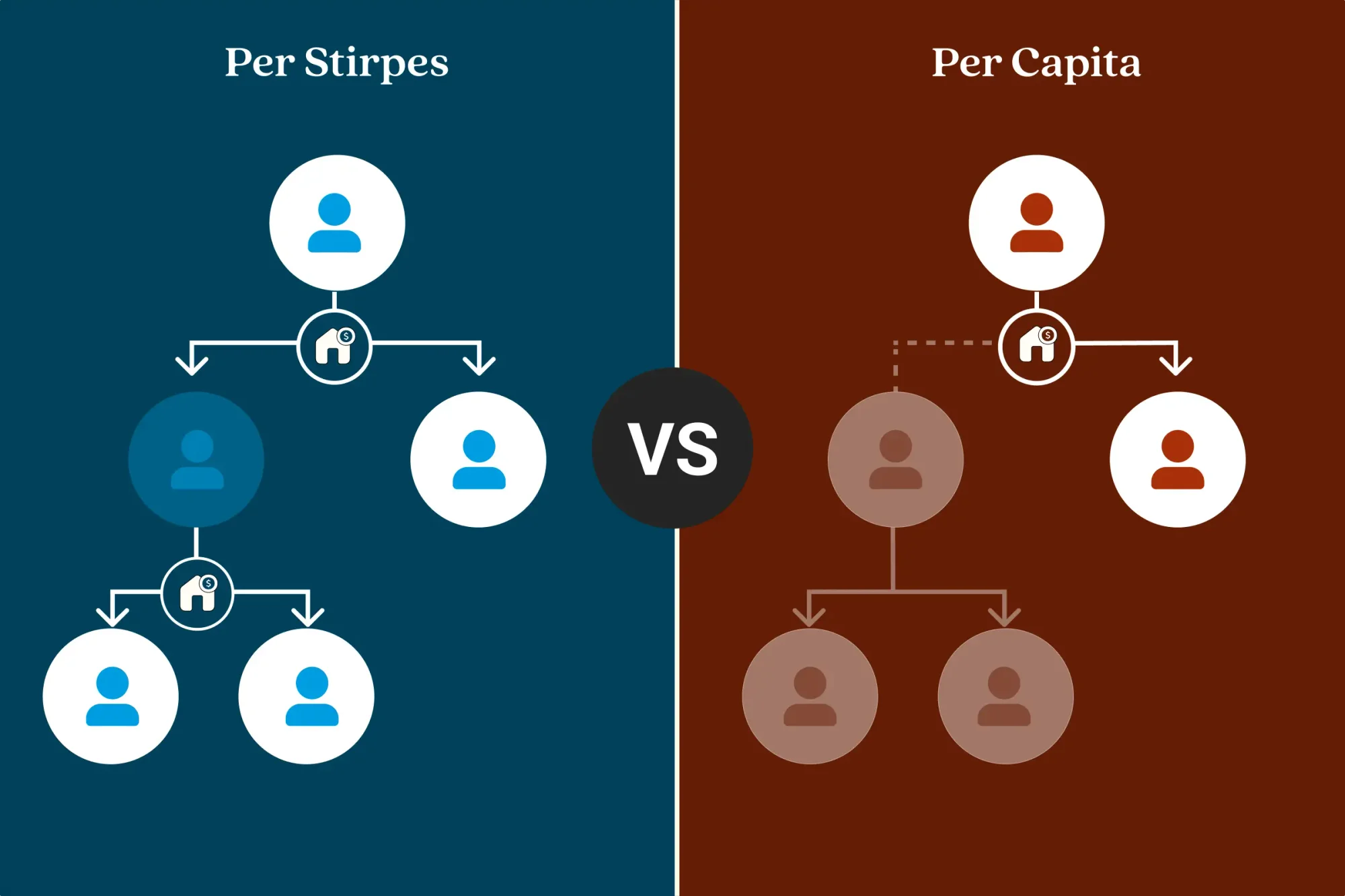

When you have multiple beneficiaries at the same or different levels, it’s important to consider not just the percentage or amount each person receives, but also what happens if a beneficiary passes away before you. This is where distribution methods like per stirpes and per capita come into play.

1. What does per stirpes beneficiary allocation mean?

Per stirpes beneficiary allocation is a type of allocation wherein, when the actual named beneficiary dies before the testator, their allocated assets are passed down to their direct descendants. In simpler terms, it means each beneficiary’s share passes to their descendants, typically their children, in equal parts. For example, imagine John has three children: Anna, Ben, and Chloe, as beneficiaries per stirpes. If Ben passes away before John, his share (1/3) doesn’t get redistributed to Anna and Chloe. Instead, it goes equally to Ben’s children, which means John’s grandchildren, as well as Anna and Chloe, will receive their allocated shares.

2. What does per capita beneficiary allocation mean?

Per capita asset distribution is calculated “by head,” or “per head,” distribution, which means, when there are two or more actual named beneficiaries, and if one of them dies, who is survived by a child, then the asset will be redistributed equally among all surviving beneficiaries.

For instance, consider the following scenario:

Rebecca (the testator) has two children, Amy and David, with David having two children of his own (Ben’s child 1 and Ben’s child 2, or Rebecca’s grandchildren). Rebecca has decided to distribute her $300,000 investment amount equally to her two children, Amy and David. But David died before Rebeccaand couldn’t receive this amount. According to the per capita distribution, the $300,000 will be equally redistributed to all living beneficiaries at the time of distribution: This would include Amy, Ben’s child 1, and Ben’s child 2. Each of them will receive:

- Amy: $100,000

- Ben’s child 1: $100,000

- Ben’s child 2: $100,000

3. Key differences between per stirpes and per capita allocations

| Key aspects | Per Stirpes | Per Capita |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution method |

By family line/branch | By individual head count |

| When the beneficiary dies |

Share passes to their descendants |

The share is redistributed equally among all surviving beneficiaries |

| Inheritance Rights | Maintains family lineage structure |

Treats all living beneficiaries equally, regardless of generation |

| Generation Impact | Preserves generational allocation |

Flattens the generational hierarchy |

4. What happens if you don’t specify beneficiary allocation?

If you name multiple beneficiaries but don’t specify how much each should receive, most financial institutions will automatically split the asset equally among them. This might not reflect your true intentions.

Then there can be a scenario where you might have mentioned exactly how much amount or percentage share you have allocated to your designated primary and contingent beneficiaries, but due to some human/manual error, it might not add to a total of 100% or the full amount in your account. For instance, consider you have $112,500 in your IRA account, and you have allocated $50,000 to your elder son Jacob and another $50,000 to your daughter Janet. However, according to the total amount, there is still a $12,500 balance that is lying unallocated in your IRA. This is often considered an oversight or error in the beneficiary designation process.

Financial institutions generally require the total allocation to equal 100%. If it doesn’t, the unallocated portion may be handled according to the institution’s default policies, which can include passing the remainder to your estate or dividing it among surviving beneficiaries. This is why it’s essential to ensure that all allocations add up to 100% to avoid confusion or unintended outcomes.

Another scenario: If the primary beneficiary is no longer living and there’s no contingent or alternate plan, or any portion of the asset that is not covered by a beneficiary designation (due to an allocation error or all beneficiaries being deceased with no alternates), then it will revert to your probate estate. At that point, the asset is no longer distributed by beneficiary designation but instead becomes part of the general estate assets. The probate court will then oversee its distribution according to your will, or if there is no will, according to state intestacy laws. So, in such cases, the court takes over to decide how the unallocated portion is distributed.

For some edge cases, if one of several named beneficiaries is no longer living and there is no contingent beneficiary named for a particular share or account, some institutions will automatically redistribute the deceased beneficiary’s share equally among the surviving named beneficiaries (according to the per capita method). However, not all institutions follow this practice, and it may depend on the account agreement or state law.

5. What are the best practices for setting up beneficiary allocations?

- Review and update allocations regularly, especially after life changes like marriage, divorce, births, or deaths.

- Double-check that your percentages add up to 100%.

- Coordinate your allocations across all accounts, trusts, and estate documents for consistency.

- Clearly define backup (contingent) beneficiaries and their allocations.

How to change beneficiaries?

Beneficiaries don’t have any legal rights to your assets during your lifetime—and may not even know they are your beneficiaries—so you can feel free to adjust and change the designations on your life insurance policies and retirement accounts as often as you want, with one notable exception: If the account is irrevocable, you cannot change beneficiaries.

Retirement accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s make it easy to change designated beneficiaries. Since this could have serious tax consequences, particularly where spouses are involved, it's important to consult a legal or tax professional to make sure your affairs are arranged in the most advantageous way possible.

Remember that an estate plan is, rather ironically, a living and breathing document. That means you should review it regularly to make sure all of the provisions still communicate what you want to happen to your assets upon your death. Whenever you or loved ones experience a life event or change, you should revisit not only your will and any trusts but also your life insurance policies and retirement accounts to make sure you have named your chosen beneficiaries—both primary and contingent. Also, if you’ve had a change of heart about who you want to inherit your assets, it’s time to update your beneficiaries.

It’s impossible to plan for all possible eventualities, but with the advice of an experienced estate planner, you can make sure you have arranged your affairs to best reflect your wishes and rest easy knowing that your estate will be handled with ease once you're gone.

Understanding primary beneficiaries

As mentioned before, a primary beneficiary is the individual or entity first in line to receive assets from your will, trust, life insurance policy, or financial account upon your death. This designation ensures your assets are distributed according to your wishes. Understanding the role, rights, and best practices for naming a primary beneficiary is essential for effective estate and financial planning.

1. Who can be a primary beneficiary?

Essentially, anyone you trust to receive your assets can be named as your primary beneficiary. However, the designation should align with your financial goals and family dynamics. In most cases, primary beneficiaries are the closest person to the asset holder, typically their spouse or domestic partner.

Some other options include:

- Children (including stepchildren, minors, though special rules may apply for minors)

- Other family members (siblings, parents, grandchildren)

- Friends or trusted individuals

- Charities or nonprofit organizations

- Trusts or legal entities

The only major restriction is that beneficiaries must be legally competent to accept the inheritance. If you name a minor, a court-appointed guardian or a trust will typically manage the assets until the child reaches adulthood.

2. How to designate a primary beneficiary?

Follow this process and be aware that certain legal requirements are needed when designating a primary beneficiary.

- Specify the identification details clearly: When opening a financial account or purchasing a policy, you’ll be asked to name your primary beneficiary. Use full legal names and, if possible, Social Security numbers to avoid confusion in identifying the right beneficiary.

- Check whether the beneficiary can legally be named: The beneficiary must be able to legally accept the asset. For minors, appointing a guardian or creating a trust is recommended.

- Get spousal consent: In some jurisdictions, especially with retirement accounts, you may need written spousal consent to name someone other than your spouse as primary beneficiary.

- Distribute precisely: Specify the percentage or portion each beneficiary should receive. For instance, if there are multiple primary beneficiaries, and if you’re not specifying the percentage or the exact amount each beneficiary should have, chances of disputes and confusion may occur.

- Verify and document beneficiary update details: You must update your beneficiary details if any life-changing situations happen, such as death, divorce, or other relationship disputes. Updating or cross-checking your beneficiary details regularly can help to avoid unnecessary chaos. Also, it's a good practice to sign and date the form whenever you’re updating or changing your beneficiaries.

3. How many primary beneficiaries can you have?

You may name multiple primary beneficiaries and specify the percentage share or amount each should receive. This flexibility allows you to tailor your plan to your family structure and personal wishes. Clearly state what share each should receive (e.g., 60% to your spouse, 40% to your child) and ensure the total adds up to 100%.

4. What happens if a primary beneficiary dies before the insured?

If a primary beneficiary dies before you (the account holder or insurer) and you do not update your designations, their share typically:

- Goes to other named primary beneficiaries, if any, in proportion to their allocations.

- Passes to a contingent beneficiary if the designated primary beneficiaries are also unavailable.

- If there are no primary, contingent, or tertiary beneficiaries named by the account holder, the asset may revert to your estate, potentially triggering probate.

Best practice: Regularly review and update your designations to reflect changes in life circumstances.

5. What if the insured and primary beneficiary die simultaneously?

In rare but critical scenarios, such as a shared accident, if both the insured and the primary beneficiary die at the same time, distribution depends on whether insurance proceeds are determined by state law or by a “simultaneous death clause” in the policy. Many states, such as Washington, follow the Uniform Simultaneous Death Act, which presumes that if it cannot be determined who died first, the insured is considered to have survived the beneficiary. In this case, the policy proceeds would go to any named contingent beneficiary. If no contingent beneficiary is listed, the proceeds typically revert to the insured’s estate, where they are distributed according to the will or state intestacy laws, often involving probate. Including a common disaster or simultaneous death clause in your policy can help avoid complications and ensure your assets are distributed according to your wishes in these rare but critical scenarios:

6. Why is it important to keep your primary beneficiary details updated?

Keeping your beneficiary designations current is essential because these instructions override your will for most accounts and policies. If your life circumstances change and you fail to update your beneficiaries, your assets may go to unintended recipients, or your estate may face delays and legal challenges. Regular reviews ensure your assets are distributed as you intend and minimize the risk of family disputes or probate complications.

Understanding contingent beneficiaries

Though often overlooked, contingent beneficiaries play a critical role in comprehensive estate and financial planning. They provide an extra layer of security to ensure your assets are distributed according to your wishes, even if life takes an unexpected turn.

1. Who can be a contingent beneficiary?

A contingent beneficiary, sometimes called an alternate beneficiary, can be:

- A person (children, other relatives, friends)

- An organization (nonprofit, religious group, foundation)

- A trust or your estate

Essentially, anyone you trust to inherit your assets in case your primary beneficiary is not available. However, eligibility might depend on local laws, especially when it involves minors or institutions.

2. How to designate a contingent beneficiary?

Designating a contingent beneficiary is typically done at the same time you name your primary beneficiary, using a standard beneficiary designation form provided by insurance providers, financial institutions, or estate attorneys.

2.1. What steps should you follow while naming contingent beneficiaries?

- Obtain the correct form from your life insurance, retirement plan, or estate planner.

- List the full legal name, relationship, and identifying details (like Social Security Number or birth date) of the contingent beneficiary.

- Specify the conditions under which the contingent would inherit (e.g., only if the primary predeceases you or refuses the asset).

- Indicate the allocation, especially if naming multiple contingent beneficiaries.

- Sign and submit the form as per the institution’s requirements.

2.2. What are the legal aspects you should consider while naming a contingent beneficiary?

Naming contingent beneficiaries involves complex legal considerations that vary significantly by state, asset type, and individual circumstances. These legal requirements exist to protect both the account holder’s intentions and the rights of family members, while ensuring proper asset transfer and tax treatment. Failing to address these legal aspects can result in unintended consequences, family disputes, tax penalties, or court intervention to resolve distribution conflicts.

Laws governing contingent beneficiaries vary by state. For instance, according to the Texas Insurance Code, Texas forfeits a beneficiary’s rights if they unlawfully cause the insured’s death, passing assets to the next eligible contingent beneficiary or the estate. “Slayer rule” statutes in many states disqualify beneficiaries who murder the insured, redirecting assets to contingent beneficiaries.

a. Spousal consent for community property states

In community property states like Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, Wisconsin, naming someone other than your spouse, whether primary or contingent, may require written spousal consent. Without this consent, your spouse may claim a portion of the asset despite your designation.

b. Explicit designations in documentation

A contingent beneficiary only inherits if the primary beneficiary cannot accept the assets (e.g., due to death or refusal). However, this transfer requires clear language in your policy, will, or trust specifying the contingent beneficiary's role. Ambiguities could lead to the assets passing to your estate instead, triggering probate.

c. Arrangements for minor beneficiaries

Minors cannot legally control inherited assets. If naming a minor as a contingent beneficiary, establish a trust, custodial account (UGMA/UTMA), or appoint a guardian to manage the assets until the child reaches adulthood. Without this, the court may appoint a guardian, potentially causing delays and added costs

d. Beneficiaries should be legally eligible

Ensure your contingent beneficiary is legally capable of receiving assets. For example:

- They must be of legal age (or have a guardian in case of minors).

- Entities like trusts or charities must be valid and operational.

3. How many contingent beneficiaries can you have?

There is no legal limit to the number of contingent beneficiaries you can name. You may designate several individuals or organizations and specify the share each should receive. This flexibility allows you to tailor your plan to your unique family or philanthropic goals.

4. When and how do contingent beneficiaries receive benefits?

Contingent beneficiaries only receive benefits if:

- The primary beneficiary has died

- The primary beneficiary refuses the inheritance

- The primary beneficiary cannot be located. This means that when executors or account custodians of a life insurance policy (the insurance company), or retirement accounts (the IRS), can’t find the beneficiary, even after taking “reasonable steps” to find the missing beneficiary, like checking addresses, sending notices, or even hiring investigators. The inheritance is then distributed to the next designated person. Though there is no single federal rule specifying the exact number of years, typically, insurers will make reasonable efforts over a period defined by state law or company policy. For instance, some states, such as Virginia, allow declaring someone legally dead after they’ve been missing for seven years.

- The primary beneficiary is legally disqualified (e.g., due to divorce or criminal charges). For example, in most U.S. jurisdictions, a divorce automatically revokes previously named ex-spouse beneficiary designations unless expressly reaffirmed after the divorce; otherwise, the benefits will flow to contingent beneficiaries.

Once it’s confirmed that the primary cannot receive the benefits, the institution will follow the next-in-line structure and release the funds to the contingent as per the original designation form.

5. What happens if a contingent beneficiary dies?

If a contingent beneficiary dies before you, their share will typically be redistributed among any surviving contingent beneficiaries after your death, if you have named more than one. If no contingent beneficiaries remain and there is no other co-contingent beneficiary or tertiary beneficiary mentioned, the asset may pass to your estate, potentially triggering probate and court involvement.

Having a remote contingent beneficiary also equips one to be prepared for any unforeseen circumstances. One such possibility to address with your beneficiary designations is the unthinkable: that a tragedy could affect all of your chosen beneficiaries. You can guard against this by naming a remote contingent beneficiary, which is an entity or person who would inherit your assets should none of your other chosen beneficiaries survive you.

6. Can a minor be a contingent beneficiary?

Yes, a minor can be named as a contingent beneficiary. However, because minors cannot legally inherit assets directly, you should appoint a guardian or establish a trust to manage the inheritance until the minor reaches the age of majority. Failing to do so may result in court intervention and delays. It can even result in court-appointed guardianship, which may not align with your wishes.

7. Why is it important to keep your contingent beneficiary details updated?

Life is unpredictable. A contingent beneficiary you named five years ago may no longer be the right choice today.

Here are the reasons why you need to update the contingent beneficiaries:

- After a marriage, divorce, or remarriage

- Upon the birth or death of a family member

- Following a falling out or reconciliation with someone

- If your financial goals or charitable interests change

Comparison: Primary vs contingent beneficiaries

Understanding the distinction between primary and contingent beneficiaries is fundamental to effective estate planning, life insurance, and retirement account management. Each type of beneficiary plays a unique role in how your assets are distributed after your death, ensuring your wishes are carried out and providing a clear path for your legacy. Here’s a comparison table that explains the differences between primary and contingent beneficiaries.

What are the legal rights of beneficiaries?

In the United States, beneficiaries named in a will or trust have specific legal rights that ensure they are treated fairly and receive the assets designated to them. These rights are rooted in state probate laws, fiduciary obligations, and legal precedents such as the Uniform Probate Code (UPC), which many states have adopted in part or in full. Although the exact rights can vary slightly by jurisdiction, there are key protections afforded across the board.

Here are the core legal rights that beneficiaries should know:

1. Right to notification

Beneficiaries have the right to be informed when a probate case is opened or a trust becomes irrevocable after the grantor's death. Executors or trustees are legally required to send notice to all named beneficiaries. In probate cases, notice is governed by state probate courts. For instance, in Texas, the personal representative of the decedent's estate must notify each beneficiary named in the will whose identity and address are known to the personal representative.

2. Right to receive a copy of the will or trust

Beneficiaries are entitled to request and obtain a copy of the will (once it’s submitted to the probate court) or the trust document. Probate proceedings are public, so the will becomes part of the public record once filed.

To locate probate records, you can visit the relevant county probate court website or search federal court records via PACER.

3. Right to an accounting

Most states grant beneficiaries the right to receive a formal accounting of the estate or trust’s financial activities from the executor or trustee. This accounting must detail all assets, debts, income, and distributions. States like Florida and Texas outline this process in their probate codes, which you can review at Florida Courts or the Texas Estates Code.

4. Right to receive timely distributions

While settling an estate takes time (often months to a year), beneficiaries have a right to receive their inheritance once debts and taxes are settled. Any unreasonable delay in distribution could be grounds for legal action.

5. Right to challenge the will or trust

If a beneficiary believes a will or trust was created under duress, fraud, or undue influence, or if they suspect mismanagement by the executor or trustee, they can contest it in court.

6. Right to equal and fair treatment

Trustees and executors owe beneficiaries a fiduciary duty to act impartially and in good faith. This means no beneficiary should be favored or disadvantaged unless specifically outlined in the will or trust.

Understanding and asserting these rights can help beneficiaries safeguard their inheritance and ensure the deceased’s wishes are honored under U.S. law.

What are some common legal questions faced while naming beneficiaries?

While naming beneficiaries, you might have a lot of confusion and thoughts in mind. Some of the concerns that you might have are listed below:

1. What happens if a primary beneficiary predeceases the policyholder?

If a primary beneficiary dies before the policyholder and no contingent beneficiary is named, the asset typically passes to the estate and is distributed according to the will or state intestacy laws, which may trigger probate and additional taxes. Regularly updating beneficiary designations helps avoid this outcome.

2. What happens if disputes arise among multiple beneficiaries?

If disputes arise among multiple beneficiaries, they can lead to delays in asset distribution, legal battles, and even probate litigation. Common reasons for conflicts include unequal inheritances, vague wording in the will or trust, accusations of undue influence, or executor misconduct. These disputes may be first addressed through mediation, but if unresolved, they may escalate to probate court, where a judge can interpret the will, resolve the conflict, or even appoint a new executor. During this time, asset distribution may be paused. To minimize such issues, it’s important to use clear language, communicate intentions during life, and keep estate plans updated.

3. Is there any difference in beneficiary rules by insurance providers?

Each insurance company or financial institution may have its own requirements for naming, updating, or contesting beneficiary designations. It’s important to understand these rules and work with your provider to ensure your designations are valid and reflect your intentions.

What are the tax consequences that beneficiaries can face?

While inheritances are generally not considered taxable income under U.S. federal law, certain types of assets and state-level taxes can create complex tax obligations for beneficiaries. Below is a breakdown of the key tax consequences beneficiaries should be aware of.

1. Federal estate tax

The federal estate tax applies to estates with a total value exceeding the exemption threshold of $15 million for individuals in 2026. The tax is paid by the estate, not the beneficiaries directly. For the latest tax exemption thresholds (which change every year), you can check the IRS Estate Tax page.

2. State-level estate and inheritance taxes

While there is no federal inheritance tax, some U.S. states impose estate or inheritance taxes. These vary by state and relationship to the deceased. As of 2026, five states levy an inheritance tax, including Maryland, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The rate of taxation can vary by relationship to the deceased; closer relatives often receive exemptions or lower rates. You can easily check your state’s laws via the Tax Foundation Guide.

3. Income tax on certain inherited assets

Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s: If you inherit a traditional IRA or retirement account, you may be required to pay income tax on distributions. Under the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019 (SECURE Act of 2019), most non-spouse beneficiaries must fully withdraw inherited retirement accounts within 10 years.

Roth IRAs: Roth IRAs are usually tax-free, provided the account meets certain conditions before the original owner’s death.

Life insurance: Life insurance proceeds are generally tax-free for beneficiaries.

Annuities and bonds: These may also trigger taxable income depending on the structure and how payments are received.

4. Capital gains tax

When inheriting assets such as real estate or stocks, beneficiaries typically benefit from a “step-up in basis.” This means that if you sell the asset shortly after inheritance, the capital gains tax is typically minimal.

If the asset appreciates after the date of death and is later sold, the beneficiary may owe capital gains tax on the post-inheritance increase.

5. Gifts received before the decedent’s death

If the decedent gifted you assets before death, the gift tax may apply instead of inheritance or estate tax rules. While gift taxes are generally paid by the donor, it’s important for beneficiaries to track such gifts to avoid audit issues. You can always review the IRS Gift Tax Page for further clarification.

Given the legal and financial complexity involved in estate distributions, it’s highly recommended that beneficiaries consult with a qualified estate planning attorney or tax advisor. Doing so can help them navigate U.S. probate law and minimize gift tax liabilities while honoring the intentions of the deceased.

We’ll help guide you through your estate plan—whether you need a will or trust.

What overrides what? Beneficiary designations, wills, trusts, and spousal rights explained

When planning your estate, clarity is everything, but things can quickly become complicated when different legal tools conflict. One of the most common areas of confusion involves beneficiary designations, wills, trusts, and spousal rights. Each plays a crucial role in how your assets are distributed after death, but not all carry equal legal weight.

1. What are beneficiary designations?

Beneficiary designations are instructions you give directly to financial institutions or insurers about who should receive a specific asset after your death. These designations are typically associated with:

- Life insurance policies

- Retirement accounts (401[k], IRA)

- Annuities

- Payable-on-death (POD) or transfer-on-death (TOD) bank and investment accounts

These designations form a contractual agreement with the provider and often bypass the probate process entirely.

a. Why do beneficiary designations take priority over wills and trusts?

In almost all cases, beneficiary designations on accounts such as life insurance policies, retirement accounts, and bank accounts override any conflicting instructions in your will or trust. This means that if you name a specific person as the beneficiary on your life insurance policy, that individual will receive the proceeds directly, regardless of what your will or trust states about that asset.

For example, if your will states that your retirement account should go to your children, but your account lists your spouse as the beneficiary, your spouse will receive the account funds. The will’s instructions are only relevant for assets that do not have a specific beneficiary designation.

b. Why do beneficiary designations take precedence?

Beneficiary designations are considered direct contracts between you and the financial institution or insurance company holding the asset. This contractual relationship is binding and bypasses the probate process, enabling faster and more efficient transfer of assets to the named beneficiary

2. Wills and trusts: Their role in estate planning

- Wills: A will is a legal document that outlines how you want your estate distributed. However, it must go through probate, a court-supervised process that can take time and money.

- Trusts: A trust is a legal arrangement that allows a trustee to hold and manage assets for beneficiaries. Unlike wills, trusts can avoid probate if assets are properly titled in the name of the trust.

While both are powerful estate planning tools, neither automatically overrides a valid beneficiary designation on file with an institution.

For instance, if you name a trust as the beneficiary of your bank account, the account will be managed according to the trust’s terms. But if you name an individual as beneficiary, that person receives the funds, not the trust, even if your trust or will says otherwise.

3. Spousal rights and legal protection

In many jurisdictions, spouses have special legal rights regarding inheritance, especially in community property or equitable distribution states. This means:

- Community property states. In community property states (like California, Texas, and Arizona), a spouse may have a legal claim to half of any assets acquired during the marriage, even if someone else is named as a beneficiary.

- Common law states. In common law states, a surviving spouse may have a right to a portion of the estate (called an elective share), which can sometimes challenge the terms of a will but not always override a beneficiary designation.

If spousal rights are not properly addressed, a spouse may be able to challenge or override a beneficiary designation in court, particularly if they were not given the opportunity to consent to the designation.

Our platform helps you create or update your plan—step-by-step, with attorney support when you need it.

Final thoughts: Choosing the right beneficiaries is more than a formality

Designating beneficiaries may seem like a simple checkbox on a financial form, but as this article has shown, it’s one of the most crucial decisions in your estate and financial planning. Whether you’re naming a primary, contingent, or tertiary beneficiary or coordinating designations across multiple accounts and documents, the choices you make today will shape how your assets are transferred and how your legacy is preserved.

By understanding the differences between various types of beneficiaries, the legal precedence of designations over wills and trusts, and the tax implications that can arise, you’re already taking meaningful steps to protect your loved ones and minimize the risk of confusion, conflict, and court intervention.

FAQs

1. Can a beneficiary be both primary and contingent?

No, a beneficiary cannot hold both roles for the same asset or policy. A primary beneficiary is the first in line to receive benefits upon the account holder’s or policyholder’s death. A contingent beneficiary only receives the asset if the primary beneficiary is unable to (e.g., they have died or cannot be located). However, the same person can be named as a primary for one account and a contingent for another.

2. How to change or remove a beneficiary?

Changing or removing a beneficiary is a straightforward process:

- Request a change form from your insurance company, bank, or retirement account provider.

- Fill out the form completely, indicating the new beneficiary or removal.

- Submit the form to the respective institution.

- Verify confirmation, and keep a copy for your records.

Note: If the asset requires spousal consent (e.g., 401[k] plans), you may need your spouse’s notarized signature to make changes.

3. What is the difference between allocation and percentage for beneficiaries?

Allocation and percentage both refer to how assets are divided among beneficiaries, but the terms are used slightly differently:

- Percentage. You specify exactly what percent of the asset each beneficiary receives (e.g., 50% to each of two children).

- Allocation. This can refer to either percentages or specific dollar amounts. It is the broader term for how you divide the asset among multiple beneficiaries.

Both methods ensure clarity in how your assets are distributed and help prevent disputes.

4. What is the difference between a dependent and a beneficiary?

A dependent is someone who relies on you financially, such as a child or spouse, and may qualify for certain tax benefits or insurance coverage. A beneficiary, on the other hand, is any person or entity you name to receive your assets or benefits upon your death. A dependent can be a beneficiary, but not all beneficiaries are dependents.

5. How do you know if you’re a beneficiary?

Typically, you’ll be notified by the institution (like an insurance company or financial provider) after the policyholder’s death. To find out:

- Ask the account or policy owner directly, if appropriate.

- Check with the estate attorney or executor after the person passes.

- Review the deceased’s records, which may include account statements or beneficiary forms.

Please note that the financial institutions do not disclose this information while the policyholder is alive unless you're authorized.

6. Who is the sole beneficiary?

A sole beneficiary is the only person or entity named to receive an asset or benefit upon the owner’s death. There are no contingent or secondary beneficiaries listed. This simplifies distribution but can be risky if the sole beneficiary also passes away, which can potentially trigger probate.

7. What is a beneficiary for life insurance?

A life insurance beneficiary is the person or entity you designate to receive the death benefit from your life insurance policy when you pass away. You can name one or multiple beneficiaries and specify how the payout should be divided among them.

8. What is the difference between a successor trustee and a beneficiary?

- A successor trustee is the person appointed to manage a trust after the original trustee dies or becomes incapacitated. Their role is administrative and fiduciary.

- A beneficiary is the person (or entity) who receives assets or benefits from the trust.

In some cases, the same person may be both trustee and beneficiary, but their legal responsibilities and entitlements differ.

9. What happens if there is life insurance with no beneficiary?

If no beneficiary is named, the life insurance proceeds typically become part of the policyholder’s estate. The funds are then distributed according to the will or, if there is no will, according to state intestacy laws. This process may involve probate, which can delay the payout and reduce the amount received due to court costs and fees.

Michelle Kaminsky, Esq., contributed to this article.